In 1913, partners – Charles Grinnell Ashley and James Bradley Crippen – disembarked at old Union Station, ready to start afresh in a new city after leaving behind their hometown of Chicago. Like many immigrants arriving in Toronto, they were seeking new opportunities, and a chance to reinvent themselves. Building on a foundation unburdened from the past, Charles and James would become two of the most significant figures in 20th-century photography in Toronto as well as patrons of modern art and architecture, and pushed the boundaries of what Toronto’s infamously “gentile” society was willing to accept – or perhaps just ignore – in order to stay fashionable.

In 1913, partners – Charles Grinnell Ashley and James Bradley Crippen – disembarked at old Union Station, ready to start afresh in a new city after leaving behind their hometown of Chicago. Like many immigrants arriving in Toronto, they were seeking new opportunities, and a chance to reinvent themselves. Building on a foundation unburdened from the past, Charles and James would become two of the most significant figures in 20th-century photography in Toronto as well as patrons of modern art and architecture, and pushed the boundaries of what Toronto’s infamously “gentile” society was willing to accept – or perhaps just ignore – in order to stay fashionable.

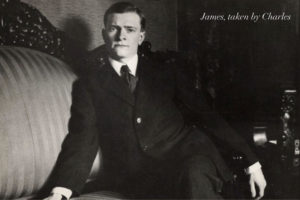

Charles, who was 34 upon arrival, was an electrical engineer born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, while James, 25, was born in the nearby town of Coldwater. By 1910 Charles and James were living together on Jefferson Avenue in Chicago – what motivated their move to Toronto I’m not sure, although it’s unlikely a coincidence that at the same time the two famous female sculptors, Francis Loring and Florence Wyle – who had spent time in Chicago – moved to Toronto around the same time. Francis and Florence had in 1911 been “outed” by an instructor at the Art Institute of Chicago, which certainly would have hastened their move from the city.

Pre-war Toronto wasn’t exactly a hotspot for queer culture or queer-friendly – the police’s Morality Department, established in 1886, enforced a social purist vision and sought to uphold the city’s moniker, “Toronto the Good”. This included cracking down on homosexual acts, interracial relationships, and businesses that operated on Sundays, among other perceived “illicit” activities.

Pre-war Toronto wasn’t exactly a hotspot for queer culture or queer-friendly – the police’s Morality Department, established in 1886, enforced a social purist vision and sought to uphold the city’s moniker, “Toronto the Good”. This included cracking down on homosexual acts, interracial relationships, and businesses that operated on Sundays, among other perceived “illicit” activities.

Nonetheless, queer spaces, communities relationships still flourished in the city, and Toronto’s deeply entrenched protestant society would more often than not prefer to turn a blind eye than cause a scene when it came to what happened behind closed doors. This rang especially true when it involved those within their social milieu. It was within this fraught context that Charles and James, along with Francis and Florence, moved to Toronto, living together and establishing a portrait studio on the eve of the first world war.

Research into Ashley & Crippen – the photography studio established by the couple – is sorely lacking, however their influence and popularity was unrivaled in Toronto through the 1920s and 30s. The two not only photographed celebrities, politicians, and members of high society, but were the go-to studio for thousands of Torontonians for their wedding, graduation, year book and family photos.

Photographic portraiture often has a detached, frozen and painfully-posed look, which is in stark contrast to their photos. Perfectly framed and lit, with a sense of depth and a true understanding of the image their subjects wanted to convey, the couple set a new bar for portrait photography in the city.

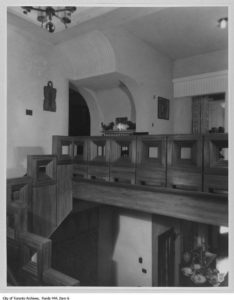

In addition to elevating the quality and popularity of portrait photography in Toronto, Charles and James should also be recognized as two of the earliest patrons of modern architecture. In 1929 the two men retained the architects Lawrence Counsell Martin Baldwin and Gerald E.D. Green to design a new photography studio on Bloor Street in Yorkville. Baldwin & Green were themselves highly important yet underrated early modern architects who designed a number of significant buildings in Toronto. After the Depression Baldwin became a curator at the fairly new Art Gallery of Toronto (now the AGO), and would go on to be a significant advocate for heritage conservation in the city.

The Ashley-Crippen Studio was a complete design inside and out; unfortunately time hasn’t been friendly to the building, and while it technically still stands on Bloor Street its facade and interior have all but been replaced by successive waves of tenants.

The Ashley-Crippen Studio was a complete design inside and out; unfortunately time hasn’t been friendly to the building, and while it technically still stands on Bloor Street its facade and interior have all but been replaced by successive waves of tenants.

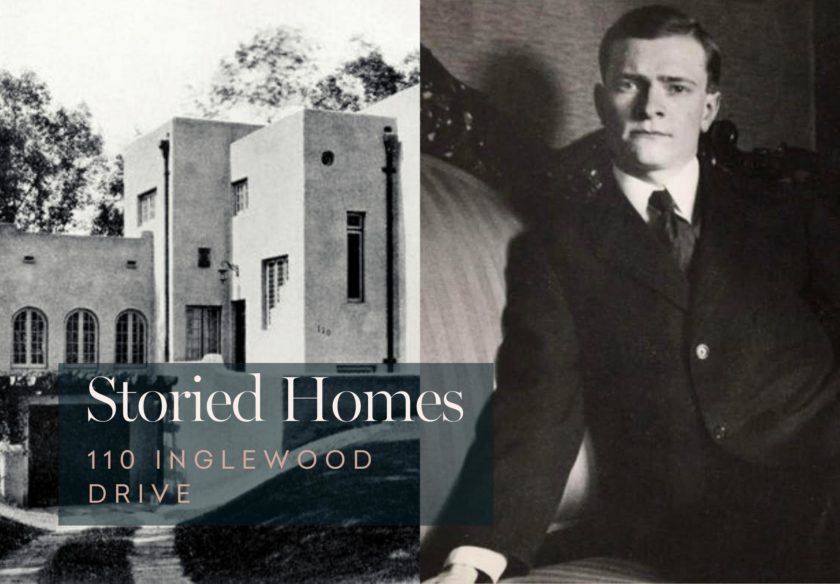

In 1922 “The Boys”, as they were often called, moved to the leafy suburb of Moore Park. An interesting choice for two gay men who were living together, perhaps, but at that time the neighbourhood was still lightly populated, and I’m sure would have afforded them more privacy than downtown’s tightly-packed neighbourhoods.

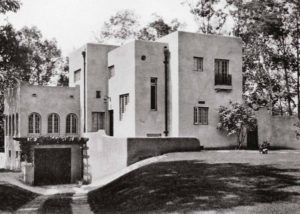

Their house on Inglewood Drive, tucked far back and perched on the edge of the Vale of Avoca, is, like its first owners, truly unique in the city. The design is credited to “A.E. LePage and B. Kelly”, although I haven’t located any primary source confirming this, and haven’t been able to find any information about LePage and Kelly as of yet.

The house completely broke the mold for residential architecture here in Toronto, and would have no doubt caused a stir when completed. The home consists of four primary volumes, clad in stucco and pierced by relatively small rectangular windows save for the arched windows looking into the southern facing sunroom. The architects were clearly looking south for inspiration, specifically to the Spanish Colonial Revival style which was taking off in Florida and California. Of note as well is the integration of a below-grade garage, which has unfortunately been replaced and a new above-grade garage has been unceremoniously placed in the front yard.

What happened to Charles Ashley and James Crippen following the Great Depression remains a mystery; while the studio passed through various owners and still operates today, Charles and James’ story is less well known. By the 1930s they’d sold their home on Inglewood and moved into their Bloor Street studio, and by 1945 they’d moved a few blocks down the street, into a house, long demolished, that stood across from the Royal Ontario Museum.

What happened to Charles Ashley and James Crippen following the Great Depression remains a mystery; while the studio passed through various owners and still operates today, Charles and James’ story is less well known. By the 1930s they’d sold their home on Inglewood and moved into their Bloor Street studio, and by 1945 they’d moved a few blocks down the street, into a house, long demolished, that stood across from the Royal Ontario Museum.

In 1946, Charles Ashley, then 67, died after a short illness in Toronto. No funeral was announced in the local papers, and I wonder what role if any James might have been allowed to play in his funeral. A few years later, in 1951, James left Toronto for the small town of Lookout Mountain, in Tennessee, where he died at the age of 64.

Charles’ and James’ story – two men in the early 20th century who lived together for over three decades – might seem like a rarity, however I think most of us would be surprised to learn how many other stories there are like theirs in cities like Toronto. The fact that their story – two incredibly talented and prolific artists who rubbed shoulders with Canada’s who’s-who – is so unknown is in part a reflection of how hidden their lives must have been, but also the bias of historians who glanced over Charles and James, or who discussed the studio without touching on the men and their relationship that built it up to such prominence.

About the Author

Alex Corey’s passion for real estate is grounded in an appreciation for home, history and community. He brings 10 years of experience in architecture and heritage conservation to his current position in real estate with the Heaps Estrin Team, and holds a master’s degree from Columbia University in historic preservation.

Growing up in Rosedale and Moore Park, Alex developed a fascination with the area’s houses and streets, a passion and admiration that has since extended to neighbourhoods across Toronto. He can often be found exploring Toronto’s ravines, walking with his dog, Billie, in his neighbourhood of Cabbagetown or seeking out the city’s hidden historic gems.